A few years ago the internet of things caused a small boom in the technology world by promising to revolutionize our lives and incorporate technology into the most unexpected fields of everyday life, from smart clothes to light bulbs and appliances that offer a range of possibilities and still learn from our daily uses. However, the thing (still) did not appear as planned.

It is undeniable that more and more the refrigerators and stoves are smart and the houses are equipped with virtual assistants, but whoever saw the IDC buzz there by 2015 knows that it did not explode as it should. Or at least it did not blow up for us humans.

That’s right, it did not give us humans, but for other living things the internet of things is going well. For years, wildlife conservation organizations have been experimenting with new technologies to find the one that would be the best way to help them monitor and protect endangered species, especially in large areas, until finally they seem to have found what they were looking for.

Thus was born the perfect marriage. Several organizations are using the internet of things to raise data on animals and hand them over to the rangers who will thus be able to intercept the poachers before they commit their crimes.

And what is the best place to find endangered animals and large areas to be monitored? Africa, of course, where illegal trade in animals is endangering animals, such as rhinos, elephants, monkeys and even lions. That’s where the good news comes from.

What is Internet of Things?

The use of technology to stop poaching is not new. Measures such as that of British mobile operator Vodafone, which uses IDC to help preserve Scottish seals and dugongs threatened with extinction in the Philippines, are already known and show great results, but when it comes to using these means in Africa, the task it’s a little bit different.

The continent is gigantic with animals of great value on the black market (the rhinoceros horn is more expensive than gold), it lacks adequate infrastructure for large network topologies and connections and hunters are extremely furtive. So a hand that is qualified to protect the animals is more than welcome.

And the help has come on time, the rhinos that say so. While the black rhino recovered from near extinction in 1995 by doubling its population from less than 2,500 animals to approximately 5,000, today, the Black Rhino West was declared extinct in 2011 and the last North Rhino died in March of this year in Kenya . The predictions are also not encouraging: An estimated three rhinos die at the hands of horn-smugglers every day in Africa. If the rhythm continues, the rhinos will be extinct from the planet by 2025.

Rhinos, of course, are not the only ones who need help. Elephants, for example, had their population decreased by about 30 percent on the savannah between 2007 and 2014; a loss of 144,000 animals – 1 dead elephant every 14 minutes !! The data are from the Great Elephant Census (GEC), a survey conducted by Vulcan Inc. (a philanthropic company created by Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft) that scoured the entire African continent behind mammals. Data also show that the rate of decline of the elephant population is 8% per year and ivory hunters, of course, are the main reason for this killing.

A mother and a puppy of abandoned rhinos after being killed and having their horns ripped out in South Africa

A mother and a puppy of abandoned rhinos after being killed and having their horns ripped out in South Africa

But at least good news after those two paragraphs and that heartbreaking image and causing depression in anyone: network and sensor technology, in combination with analysis, now offers ways to closely monitor the populations of these animals and intercept any apparent threat.

In general, the process consists of connecting sensors to the cloud (be it public or private) through low-power networks and having these “technology patrols” provide essential information about the human activities that are detected in the area where the protected animals. With these data and alerts in hand, the patrollers (actually, this time) quickly reach the hunters before they can do any damage.

Specifically we have two projects of great success and that we will know now.

Help comes from above

For some years the Air Shepherd program maintained by The Lindbergh Foundation uses a combination of drones and analytical data in an experiment in South Africa to protect rhinos and elephants.

The data captured by the sensors of the drones are subjected to intelligent processing that builds a model of the habitual behavior of the animals around and within the monitored area. Thereafter, if some abnormal pattern-based movement is detected in the rhinos or if any suspicious human approach occurs, the drones are placed in the air to show the rangers in real time what is happening on the spot suspect.

Although it has some downsides, such as the requirement of well-trained pilots and the fact that they are sometimes on routine flights and fail to respond to a danger alert, Air Sheppard has already saved lives. With such success they have already been able to expand the protection program for Malawi, South Africa and Zimbabwe through collective funding. The next locations are Botswana, Mozambique and Zambia.

One of the drones used by Air Sheppard

One of the drones used by Air Sheppard

Fashion protection

Another promising initiative comes from the partnership between the University of Wageningen in the Netherlands and IBM who intend to help the rhinos of the Welgevonden Animal Reserve, also in South Africa, with as little intervention as possible in their daily lives. This way they do not intend to track the rhinos directly, but rather what is in their surroundings. For example, their prey.

The plan is to put a necklace (which is under development) on reserve herbivorous herds, such as zebras, impalas and gazelles, and then observe the hunting habits of rhinos. By assessing variations in their movements it will be possible to identify abnormal patterns of behavior that indicate the different types of contact they may have, such as natural predators, tourists or poachers.

-

What is a backbone?

Once captured, data will be transmitted via 3G from necklaces to the IBM Watson system operating in the cloud – Watson is one of the world’s most advanced artificial intelligence systems – and is being trained to identify the animals’ routine.

Although the IBM Watson solution has been effective so far, it has a tricky downside to being fully resolved: It is dependent on a constant connection to the cloud, which is a problem in much of Africa, especially in areas of life wild – where there are only the slow satellite connections and one or another cell tower that can not handle the message. One way out would be to use the own private wireless networks that were within reach to form a backbone , which would not solve the problem fully, yet some kind of final connection would still be needed for the IDC devices in the animals to “talk” with the cloud-based system.

Rhino tusks will also be monitoredBest of all

Rhino tusks will also be monitoredBest of all

And finally the flagship initiative to date: Connected Conservation , a program sponsored by Dimension Data and Cisco, the world’s largest manufacturer of networking and connection equipment.

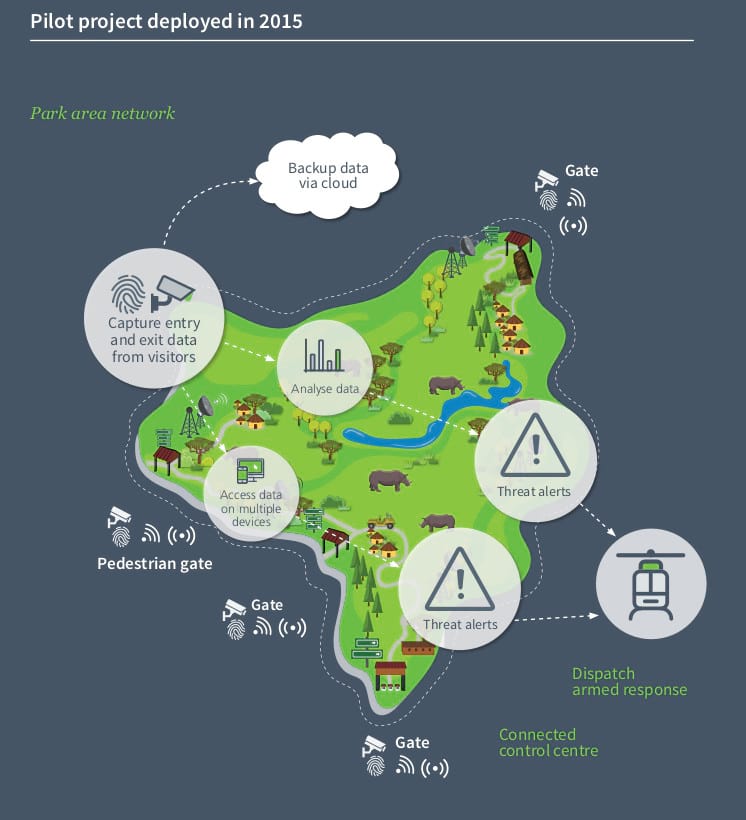

Launched in 2015, the program has used the internet of things to track people close to and within the perimeter of a particular rhino reserve in South Africa (whose name is secret for security reasons). With security camera techniques, biometric scanning, floor motion sensors, ambient heat maps, drones and a fixed radio network the program has worked well and is poised to expand to other conservation areas across the continent.

In Connected Conservation Google Analytics is the one who generates the alerts based on the detected activity patterns and sends them to the forest guards who move to the perimeter to intercept intruders. Here the only part in the cloud is a local server that connects to Microsoft’s Azure services to back up critical data regularly. Other than that the whole system is operated locally.

Companies now design a security solution for the reservation. One of the first components – installed in December 2015 – was a new point-to-point radio based network that has a speed of 50 mbps and uses towers installed at the boundaries of the park to cover the entire perimeter and function as a backbone that shares alerts video, sensors and voice communications. Wolf Stinnes, a Dimensions Data engineer, said that in addition to an uneven connection, the biggest challenge to date was torrential rain, lightning and lightning along with the heat.

In addition to the backbone of the radio network, Cisco and Dimension Data have installed wired LANs at each of the four reserve vehicle gates, monitoring cameras, biometric scanners and sensors at the gates. In addition, a wireless network was deployed throughout the reservation to provide secure Wi-Fi in the park and give guards mobile access to the data.

The initial project in 2015

The initial project in 2015

The reservation is still connected to a long-distance wireless network in the LoRa standard. Such a connection pattern is optimized for low-power devices, which enables the sensors to operate on batteries for years on end and communicate distances up to 15 km. Consequently, its baud rate is low, 27 kbps, but that’s no problem for a network that manipulates the telemetry data rate of a sensor, for example. Other tools in the system include networked thermal cameras installed along the reserve perimeter and acoustic fiber sensors.

Those who enter a vehicle, in addition to having a crawler coupled, have their plates “read” by the security cameras; the system uses a VPN connection to tap this information into a national database and know who owns the vehicles and the history of their visits. With predictive data modeling the analytical team can estimate when an individual or vehicle should get out of the reserve, “Stinnes said; if he does not come out in the planned time an alert is issued and it is verified.

And it is not just with the vehicles: Every person who passes through the gates is tracked. Biometric systems read the fingerprints of employees, rangers, animal caregivers, and suppliers; visitors already have their passports scanned.

The rhinoceros population has already grown considerably since the beginning of the

The rhinoceros population has already grown considerably since the beginning of the

And if somewhere in the park a sensor picks up a die that generates an abnormality alert and indicates a possible perimeter violation, drones can be dispatched to the alert locations to capture real-time images of what’s happening while an armed crew follows helicopter to intercept potential hunters. The new alert system has lowered the guards’ average response time from 30 to just seven minutes.

After all this cutting-edge technology we are sure that the whole process needed a lot of study and a lot of investment; but have no doubt that all this effort has already been paid. Since 2015, there has been a 96% reduction in the number of rhinos killed in the reserve, and in 2017 none of them were caught by hunters. As for the invasions in the perimeter, there was a reduction of 68%.

Upgrade to version 2.0

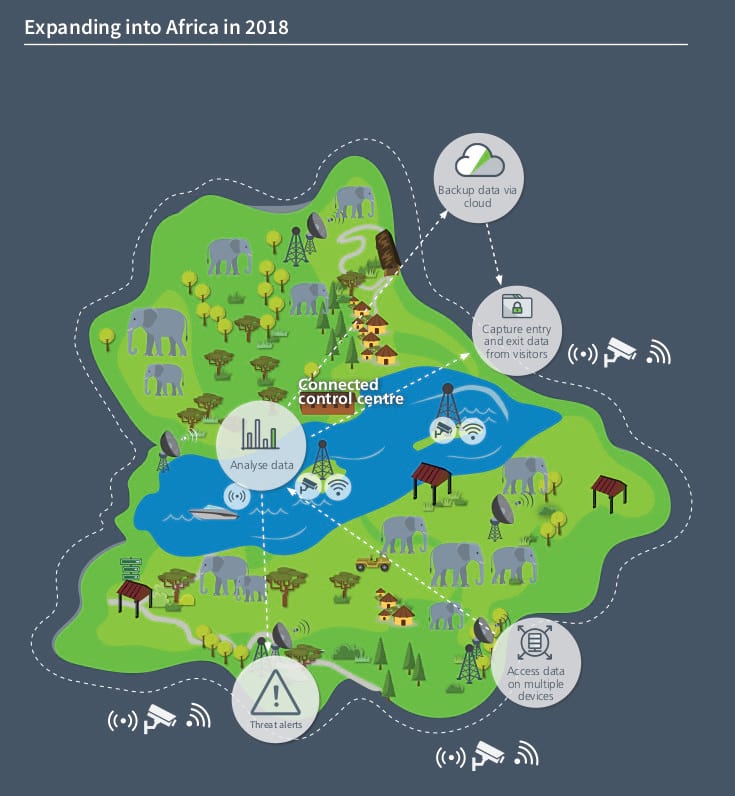

With this success that surpasses the best of expectations the Connected Conservation program now wants to expand its experience and knowledge to parks and reserves in Mozambique, Zambia and Kenya, each with its specific threats and characteristics; which makes technology need to adapt to each reality. In Zambia and Mozambique, for example, the focus should be on herds of elephants, which are being decimated at a faster rate than anywhere else in Africa.

The chosen one to receive this technological aid was a Zambian park – without name divulged also. As a whole, elephant herds in the country are generally relatively stable: out of a population of 21,758 animals in 2016, the “carcass ratio” was only 4.2% (so the proportion of dead elephants is live elephants monitored by aerial survey), but there are some places that killing is scary. For example, along the Zambezi River and in the Sioma Ngwezi National Park, on the southwest border of the country where, in the latter, the survey indicated a carcass rate of 85%, that is, 17 dead elephants for every three found alive.

What is known about this secret park that will receive help is that it will have to deal with another aggravating spot: water, not the lack of it, but rather the large amount. The site has a large lake in its interior that, in addition to being used for fishing by people living in its surroundings, is also a way of entry for hunters.

Elephants in Zambia to receive assistance from Connected Conservation

Elephants in Zambia to receive assistance from Connected Conservation

In this situation, a physical fence along the entire park is impossible. The solution will be to use a network of fixed thermal cameras mounted on radio masts as if it were a virtual fence – in addition to the usual cameras at the entrance and exit gates. The thermal camera data will be analyzed and will result in an up-to-date model that will identify movement patterns of what happens on inland waterways in and near the park. If necessary, an automatic alert will be generated for suspect boats or any night crossing that enters the perimeter.

The alerts will be received at a control center mounted on a special Zambia marine guard unit, which may send boats to intercept the hunters. To avoid harms researchers who need the lake for survival, another measure being developed is the registration and electronic identification of the same, since many hunters pass through fishing boats to enter the park.

Model employed in Zambia adapted to its particularities

Model employed in Zambia adapted to its particularities

A scalable template?

The cherry on the cake will come in time as Dimension Data and Cisco have ambitious plans to extend Connected Conservation beyond well preserved rhinos and elephants. The ultimate goal is to eliminate all forms of killing and smuggling of vulnerable animals through IDC devices and other technologies such as sharks, Asian tigers and other endangered species.

But of course this will require much more than the commitment of just two companies. In addition to constant human surveillance, agreements will have to be made with several countries and thousands of people will have to be relocated to remote environments.

Some success stories are not enough to ensure that we can save all endangered species, but if we rely on the results so far we have enough to keep us optimistic about the future. If the internet of things has not yet changed our lives, it will continue to change the lives of endangered animals.