The first time I heard the expression “immersive simulator” was Mark Brown in a video dedicated specifically to Looking Glass and the tradition of games related to the first System Shock . I remember receiving the label with a lot of rejection, what the hell did they have to simulate Deus Ex or Bioshock? The expression naturally evoked that other videogame profile represented much better by things like Euro Truck Simulator or Football Manager, games that could not be more in the antipodes of the type of experience that Hitman or the Thief saga offer.

The legacy of Looking Glass is not only evident but, far from being in a situation similar to what could happen with genres in his day prominent as the RTS or graphic adventures, is more alive than ever. The first System Shock inaugurated a school and a way of understanding the video game that comes as far as our last week, which is when it was announced and surprisingly launched Mooncrash , the new expansion of Prey. A school with personality, identity and a rich tradition, but apparently without a name. In an industry as hypersaturated as ours, being recognized is an absolute necessity. Having a title, associating with a specific genre or style and being able to present oneself quickly and effectively are as important as what is behind that name. It is clear that not everything is resolved with labels, but for a videogame, having an identity and being able to present it with clarity are of paramount importance.

And that is exactly the luck that Prey did not count on, because if there is anything worse than not having a name it is having the wrong name. And that can only get worse if in addition to having the wrong name belong to a genre difficult to identify. Ricardo Bare, chief designer and co-writer of the game (with Chris Avellone

and the director, Raphaël Colantonio) confessed in an interview that the choice of the title was something totally accidental. They presented Bethesda the project being in a fairly advanced state and they were the ones who suggested using the name of a deceased ip with which not only had nothing to do neither artistic, nor thematic, nor mechanically, but was also associated with rather unfortunate way to problematic developments. Although Prey is, in the end, a title that fits very well thematically with the game Arkane had in hand, its meaning was already occupied and referred to many other things different from itself, diluting the personality of the game. I recently read someone saying that the game should have been called Neuroshock or Psycho Shock,

But luckily Prey also deals with the need and power that resides in the ability to adapt, and it turns out that inside the Talos I, the station in which the game takes place, there is a creature that is the perfect metaphor to understand what happens with the game: the little mimics. These seemingly innocuous spiders, with their ability to steal the appearance – and also the name – of the objects that surround them, are actually the epitome of the perfect predator. His ability to mold his appearance without losing his identity, his multi-faceted and deceptively complex nature perfectly represent the character of Prey, a game that adopted a skin and a name that did not belong to him and made them his without renouncing himself. He said in his analysis that Prey is much more concerned about being a good game than looking like him, and he is right. After all, that’s what the mimics of the Talos I are dedicated to, to be a perfect threat without appearing. Arkane’s game is marked by this condition of being more than what it seems, of doing a lot with little, and of maintaining a façade that actually hides one of the most narratively rich, mechanically diverse and subtly intelligent titles that we have received in what we have from generation.

When Mooncrash was presented during the Bethesda conference last week, he did it again in a deceptive way. With a trailer marked by an openly carnivalesque tone to the rhythm You spin me round of Dead or Alive they showed a series of things that not only seemed to have nothing to do with Prey, but clashed absolutely frontal against everything that conceptually represented the original. When I heard the words “infinite replayability” and “the loot is different each game” I feared the worst: that the insufficient sales and the difficulty to communicate their identity would have resulted in a desperate attempt to reach the majority public, betraying everything that It made the first game so special and suggestive.

I could not have been more wrong.

Mooncrash, like Prey, is also a perfect imitator. Only this time the costume chosen for the occasion has been that of the roguelike. What is involved here is not to scrap the experience offered by the original to transform it into something else, but on the contrary: to take advantage of the opportunity and space that provide an extension of this type to experiment with the ideas and themes of the original , taking them even further. In Mooncrash, Prey does not recycle in roguelike, but hybridizes with it in an exquisite way, selecting and incorporating elements in his DNA with enormous precision and elegance, with the aim of adding capabilities without renouncing those he already possessed.

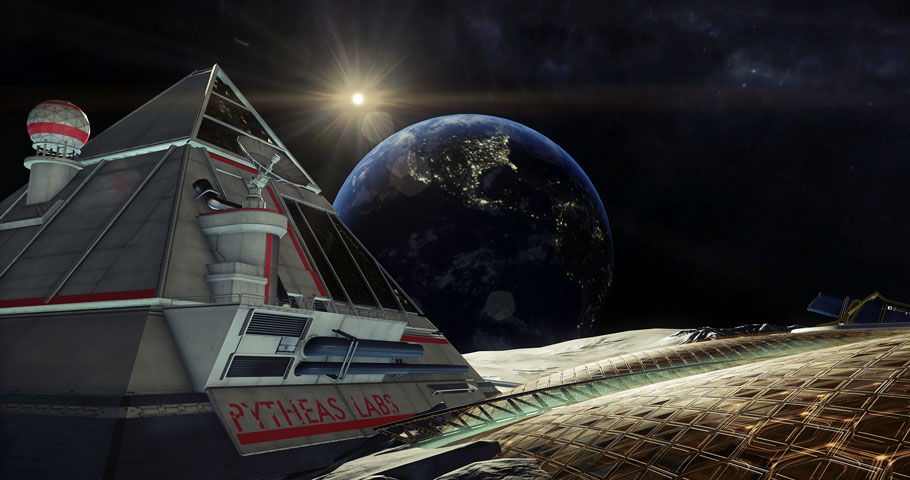

In Mooncrash we play Peter, a hacker subjected to a draconian contract by Kasma Corp., a company dedicated to corporate espionage that has set its sights on the investigations of Transtar, the protagonist of the first game, and who assigns us the task of reconstruct the information of what happened in the Pytheas moon base, property of the company, to steal their secrets from an incomplete database that they have obtained in strange circumstances. This serves as a premise to establish what really determines the core of the experience: the exploration and reconstruction of this information through simulations of virtual reality that recreate what happened on the Moon from the available information.

One of the most great things about Mooncrash is the way it has to give a narrative justification and purpose to all the new mechanical ideas it poses, and that is precisely what happens with the structure of the game and everything related to the introduction of random elements. . The idea of simulations, deceptive illusions and things that are not what they seem was something that was already present in the original game. The difference with Mooncrash is that Peter’s simulation is not perfect. Each game is actually a possible interpretation of the available data that we are examining, and that is precisely the game’s way of justifying both randomness and the need to complete the game several times. Peter’s contract is presented at the beginning in the form of a list of objectives offered by Kasma and, As we complete them, the simulation is completed. That in turn is the argument justification for the incremental development that usually characterizes games of this type. Similar to what happens in The Binding of Isaac, not only are new features, characters and variables unlocked, but also obstacles, enemies and environmental dangers that are not present when you start playing the game. The wonderful thing about Mooncrash, however, is the way it has to incorporate the rudiments of the genre at the same time that it transforms them into narrative and thematic leitmotiv, subverting what in the rest of roguelikes is simply mechanical and playable structure. Mooncrash, like the typhoons that play the game, sneaks through the gullet of the roguelike and makes it mutate to assimilate it as a part of itself.

This holistic approach to the narrative is explored in Mooncrash in an even more interesting way thanks to the adoption of multiple points of view. Unlike the original, there are five protagonists in Mooncrash, each with its own background, history and abilities. The objectives of Peter’s contract ask us to complete different tasks with each one of them, through which we are becoming involved in their respective plots, which are, in the end, what constitutes the skeleton of this DLC. As we explore what happened we are gradually giving each of the pieces that make up the puzzle of the Pytheas base, which serves as an excuse to go twisting the mechanics and go deeper into the history and background of Peter himself, in a structure vaguely reminiscent of the Animus of the Assassin’s Creed, only that infinitely better carried. This results in a narrative that places a much greater emphasis on the whole than on each of the parts and is, in the end, a much more faithful and rich way of exploring a narrative as polyhedral, complex and laminated as that of Prey. .

But the benefits of this expansion are not only in the narrative, but also have consequences in the playable. Unlike what usually happens in the more traditional roguelikes, in each game of Mooncrash we do not only carry one character, but we play with the five in succession. If we manage to escape from the station or if the character dies we move on to the next one. The interesting thing about this is that the changes we make with a character are persistent for the rest, and only disappear when we exhaust the five lives and restart the simulation. But this becomes even more attractive if we take into account that the capacities and abilities of each of the five are unique. For example Joan, the engineer, is the only one capable of repairing the doors and equipment of the station, which gives it the power to open otherwise inaccessible routes to other characters, so that escaping or dying prematurely can have a brutal impact on the fate of the other four. This adds a layer of extra complexity, and leads to the need to plan and establish a clear list of priorities and objectives before each game, and creates an absolutely fantastic tension between the strategies and plans we adopt and the need to improvise in situ before the obstacles and the unpredictability of the scenario.

But as if that were not enough, this asymmetric approach between characters also has the collateral consequence of forcing us to explore and master styles of play that we most likely leave unproven in the original, leading us to think in parallel and find creative solutions to the dilemmas presented to us the lunar base, which is, in the end, what in its purest form defines the essence of the games located in the Looking Glass tradition.

But as if that were not enough, this asymmetric approach between characters also has the collateral consequence of forcing us to explore and master styles of play that we most likely leave unproven in the original, leading us to think in parallel and find creative solutions to the dilemmas presented to us the lunar base, which is, in the end, what in its purest form defines the essence of the games located in the Looking Glass tradition.

After finishing Mooncrash I do not have the slightest doubt that it is the work of a studio with so much experience and love for that legacy that they have wanted to make it worth taking it even further, modernizing it and assuming the risk of putting it in connection with current trends, but doing it on their own terms. Mooncrash may have adopted the wicks of a fashion genre, but he has done so by seizing him and bringing him closer to himself. Because in the end, what I think defines this videogame profile is not its conservatism, but precisely its plurality and diversity. Its ability to integrate mechanics, different game styles and systems of all kinds into a coherent and seamless whole. A school and a way of making games that can only be understood from its ambition and restless character; a way of working that defines a type of video game that seems to want to do everything at the same time, in a risky and great effort to build something that, more than a piece of singular entertainment, is more like the total recreation of a miniature world , a kind of simulation that opens on our screens and allows us to immerse ourselves in a tiny universe, with its rules, its language and its particularities. It may be difficult to fix the character of something like that in a singular expression, but it is clear that Prey and Mooncrash have a clear identity and are proud members of this tradition. Maybe “immersive simulator” is not a bad name after all. is more like the total recreation of a miniature world, a kind of simulation that opens on our screens and allows us to immerse ourselves in a tiny universe, with its rules, its language and its particularities. It may be difficult to fix the character of something like that in a singular expression, but it is clear that Prey and Mooncrash have a clear identity and are proud members of this tradition. Maybe “immersive simulator” is not a bad name after all. is more like the total recreation of a miniature world, a kind of simulation that opens on our screens and allows us to immerse ourselves in a tiny universe, with its rules, its language and its particularities. It may be difficult to fix the character of something like that in a singular expression, but it is clear that Prey and Mooncrash have a clear identity and are proud members of this tradition. Maybe “immersive simulator” is not a bad name after all. but it is clear that Prey and Mooncrash are clear about their identity and proud members of this tradition. Maybe “immersive simulator” is not a bad name after all. but it is clear that Prey and Mooncrash are clear about their identity and proud members of this tradition. Maybe “immersive simulator” is not a bad name after all.